There’s a certain satisfaction to getting lost in a new city. Or your own city for that matter. The vague exhilaration of stumbling across an undiscovered gem of a restaurant, or finding a hidden staircase on your walk home. If you relate to this feeling, chances are you’ve participated in a particular kind of urban wandering often referred to as a "Dérive."

Guy Debord [image via LaRepublique]

The notion of the dérive was formalized in the 1960’s by a group of French artists and philosophers who called themselves the Situationists. Guy Debord, one of the of founders of the movement, defined the derive as “a technique of rapid passage through varied ambiences.”

[Image via BanditFox]

Evoked as both a noun and a verb, this art of “drifting” could be practiced by anyone with enough curiosity and some time to kill. The idea was to embrace randomness, intuition and chance as a means of breaking the established (and decidedly oppressive) spatial hierarchies of the city. This idea was given further resonance by the Situationist’s attempt to capture the process in a visual format, representing Paris as a series of blocks and vectors, taken out of context and suspended in a space of the surreal.

The dérive is distinct from the idea of a stroll, a hike, or a journey. Rather than being led by a destination, or even seeking the unfamiliar, the goal of the dérive is to be drawn to the various “psychogeographical contours” of the city itself. In other words, if you feel drawn to the sound of birds in the distance, let it lead your way. If the dark alley is alluring in all it’s must and mystery, walk down it. In fact, it’s even entirely possible that one could dérive by staying put in the same place all day, captivated by the peculiar power of a particular train station or tree.

But beyond being a merely poetic relic of the 1960’s, what relevant role might this idea continue to serve for urbanophiles today? One interesting thread of connection might be to consider the existence of so-called “desire paths”-the sneaky shortcuts that emerge through vacant lots and medians, creating a visual register of our collective defiance of the sidewalk.

Desire Paths in Detroit [image via FindSubstance]

Our current project in Rome has benefited greatly from unstructured wandering. We’ve done lots of official tourist activity to be sure. But in our attempts to get acquainted with the less official layers of the city, we’ve scaled fences to wander through abandoned hospital complexes, ran across bridges too narrow for a pedestrian path, and even ventured to the fringes of the city along ancient aqueducts until we could walk no further.

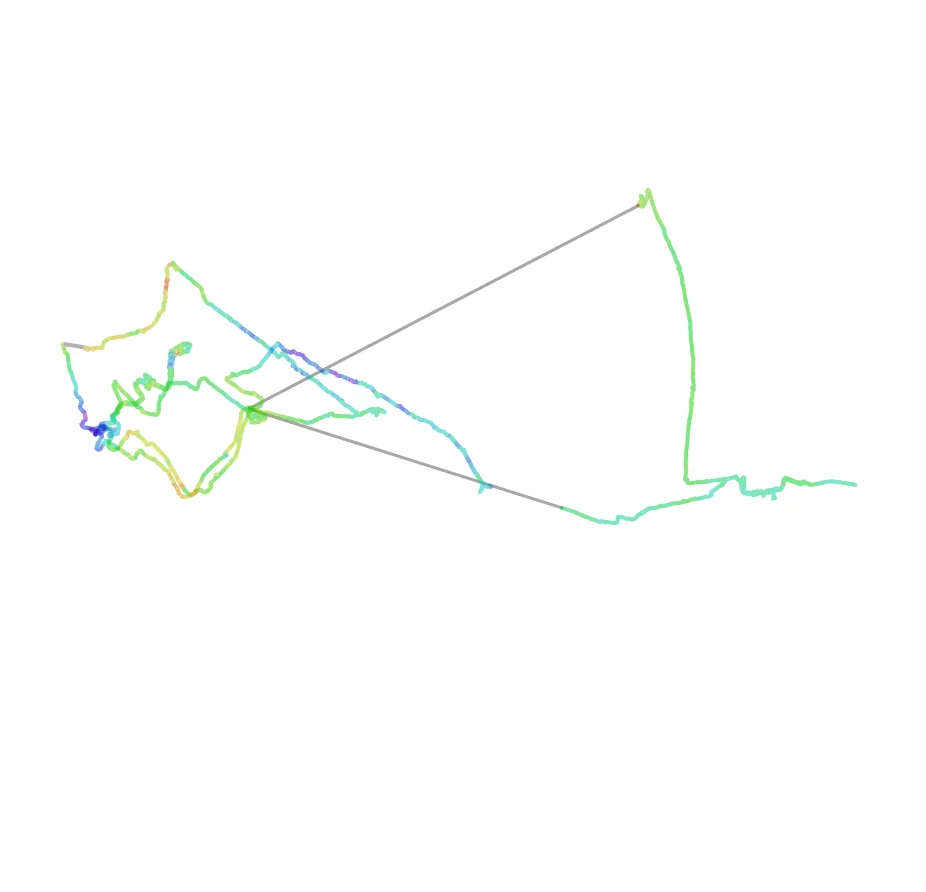

Using GPS tracking, we’ve also started to visualize some of the territory we’ve covered on foot. This process is helpful to replay and interpret back at the studio to better understand what it might mean. For example, why has our wandering been predominantly in the south and eastern parts of the city? What is yet to be discovered in the northern and western fringes?

Similarly, locative apps such as Strava have recently begun to release and visualize large data sets from their users movements to better understand how people actually circulate through urban space. It’s tempting to speculate about what new forms of “user-generated” urban design responses this could bring to bear. Pedestrian and bike paths that emerge and adapt in response to the changing needs and habits of joggers and bikers? Desire lines that define new corridors of public space in the face of future development?

Los Angeles Heatmap [image via Strava Labs ]

Next time you have a few hours to kill, rather than blow it wandering around online, consider embarking on a dérive through your own city. You may be surprised what finds you.

![Guy Debord [image via LaRepublique]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/528a7be4e4b08fd3acec9867/1414517666467-WQC9M4I500BZAXZIEVK4/image-asset.jpeg)

![[Image via BanditFox]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/528a7be4e4b08fd3acec9867/1414517678684-AFVTR25QUKSO5EKTMUEY/image-asset.jpeg)

![Desire Paths in Detroit [image via FindSubstance] ](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/528a7be4e4b08fd3acec9867/1415095770164-G2O6Q80CRG52M1BP775O/image-asset.jpeg)

![Los Angeles Heatmap [image via Strava Labs ]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/528a7be4e4b08fd3acec9867/1415095926910-T2W1AV72OQJJVJZYNEXO/image-asset.jpeg)